Discover how elite investors use Section 351 ETF conversions to move billions without triggering capital gains taxes a legal loophole reshaping modern portfolios.

When you read about new ETFs launching quietly and pulling in hundreds of millions then nearly as much flowing out days later it isn’t always about market timing or savvy asset-allocation. Sometimes, it’s about tax engineering.

Enter the world of the Section 351 conversion, the tax-code provision that’s quietly being adapted by some ultra-wealthy investors into the ETF world. The strategy? Seed a new fund with appreciated assets, list it, then restructure the holdings all without recognising immediate capital gains tax. Think of it as a “black hole” for taxable gains.

Over the past decade ETFs have become the preferred vehicle for efficiency-obsessed investors. Their in-kind creation and redemption process allows funds to swap securities for shares without selling them for cash and therefore without realizing gains. They use a piece of the U.S. tax code, originally written in the 1950s to encourage entrepreneurship, and apply it to modern ETFs.

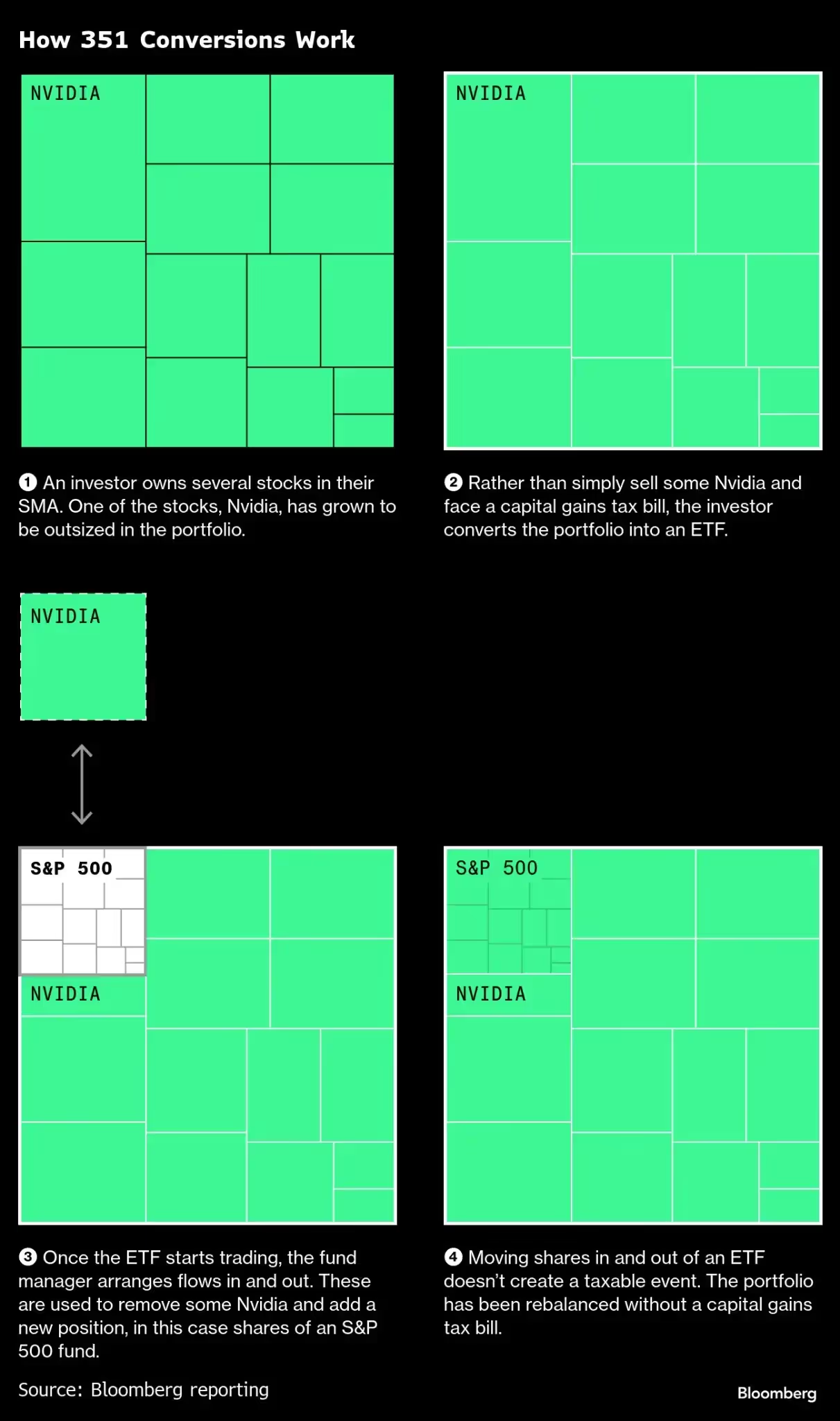

Here’s the essence:

Investors contribute appreciated assets to a new ETF and receive shares in exchange. The contribution qualifies as a non-taxable transfer under Section 351, and once the ETF is trading, its manager can rebalance the portfolio — again in-kind with no immediate tax event.

It’s a financial sleight of hand that defers taxes, keeps capital compounding, and gives portfolio flexibility that ordinary taxable accounts can’t match.

How the Trick Works Step-by-Step

- The Setup: A wealthy investor (or family office) holds a basket of appreciated stocks say 20 positions inside a separately managed account (SMA). Nvidia has skyrocketed 1,000%, making up 30% of the portfolio.

- The Problem: Selling Nvidia means realising a huge taxable gain.

- The Workaround: The investor contributes the whole portfolio in-kind to seed a new ETF. Under Section 351, the transfer isn’t taxable because it’s an exchange for ownership (ETF shares).

- The Swap: Once the ETF starts trading, authorised participants create and redeem shares using baskets of securities. The manager uses those flows to quietly remove Nvidia and replace it with, say, an S&P 500 fund all without selling for cash.

- The Result: The investor now holds ETF shares tracking a broader market exposure, and the massive gain in Nvidia remains unrealised until the ETF shares themselves are sold.

Why This Strategy Is Exploding

A. Built-In Gains Meet a Decade-Long Bull Market

After ten years of equity appreciation, many investors are “trapped” by unrealised gains. Section 351 lets them pivot without pain.

B. The ETF Wrapper’s Natural Efficiency

ETFs already avoid most fund-level capital-gains distributions. Add Section 351 and you can even change the entire portfolio with minimal friction.

C. Institutional Demand and Family-Office Engineering

Family offices crave stealth and efficiency. These conversions often launch with hundreds of millions in seed capital then go quiet once the restructuring is done.

The Legal Guardrails

The 25/50 Diversification Test

To prevent one-stock portfolios, tax rules require that no single position exceed 25% of the assets and that the top five holdings stay below 50%.

This rule explains why some conversions include other ETFs or index funds at launch they help meet the diversification threshold before rebalancing.

Documentation & Fiduciary Duty

Issuers must document a legitimate investment rationale. Converting purely for tax avoidance could draw IRS scrutiny. Managers must treat the ETF as a public vehicle, not a private shell.

The Catch: Deferred, Not Erased

Critics call these ETFs “unjustifiable black holes for capital gains.” They argue that when investors can rotate from high-tech stocks to bonds without tax, the system’s fairness erodes.

Supporters counter that it’s simply smart tax management deferral, not avoidance. The tax bill still arrives when ETF shares are sold, or disappears only upon death with a stepped-up basis.

Either way, the deferral provides an interest-free loan from the government, letting capital compound longer. In the words of Jack Bogle, it’s like “borrowing from the IRS at 0% interest.” Still, a Section 351 path carries non-trivial trade-offs. Brittany Christensen of Tidal Financial Group notes that while conversions can be effective, sponsors must weigh public-fund transparency, regulatory compliance, and fiduciary obligations. Even if a family office is the majority holder, the ETF must be managed as if anyone could be a shareholder.

Costs, Transparency, and Practical Limits

While seductive, a 351 conversion isn’t free:

- Complexity & Setup Costs: Legal structuring, fund-registration, and advisory fees can reach six figures.

- Liquidity Concerns: Early trading may show artificial flows (“heartbeat” trades).

- Higher Expense Ratios: Many conversions use actively managed ETFs with higher ongoing fees.

- Regulatory Attention: As usage scales, the IRS could revise or tighten eligibility.

Should Traders and Investors Care?

For retail traders, this strategy may be out of reach but understanding it matters. It shows how the ETF ecosystem evolves to absorb sophisticated tax needs.

For wealth managers, it’s a client-retention weapon.

For policymakers, it’s a growing blind spot in capital-gains revenue.

Ask yourself:

- Do you hold appreciated assets in a taxable account?

- Do you need diversification without triggering gains?

- Are you willing to shoulder setup costs for long-term deferral?

If so, partnering with a white-label ETF platform or tax-aware advisor could open the door to a 351 structure.

Market Practice, Not One-Offs

Issuers that court taxable investors have been early adopters of Section 351-style conversions. In several cases, funds rebalance shortly after launch using so-called “heartbeat” creations and redemptions. Example: the Castellan Targeted Equity ETF (CTEF), which launched around $370 million, exited its largest position roughly $20 million in Palantir Technologies within three days. (Castellan says it reviews positions daily and adjusts “as needed” to align with its stated objectives.)

Many conversions occur under the same money manager and continue pursuing the pre-existing strategy. But as demand broadens and multiple investors contribute appreciated assets, some ETFs begin life with a mishmash of securities that must be realigned to the prospectus.

A telling case: the Stance Sustainable Beta ETF, despite tracking a fossil-fuel-free index, was initially seeded with large Exxon Mobil and Chevron holdings that were removed within three trading days via heartbeat flows. Co-manager Kyle Balkissoon notes that rebalancing has “no hard and fast rules” and is done in consultation with counsel.

Larger issuers are showing interest, too. Avantis Investors (an American Century unit) launched Avantis US Quality ETF with about $120 million, including small stakes in other ETFs and foreign securities that were sold down within roughly a month. Recent filings indicate some funds may be seeded in-kind with low-basis securities.

According to Meb Faber of Cambria Investment Management, Section 351-style conversions can be a “perfect solution” for concentrated stockholders, direct-indexing portfolios with no losses left to harvest, or investors seeking tax-aware rebalancing. Cambria has launched two such funds so far Cambria Tax Aware ETF and Cambria Endowment Style ETF with initial assets of about $26 million and $95 million, respectively. Faber expects subsequent launches to be “sequentially bigger,” suggesting the coming year could be when 351 goes mainstream.

Policy Tension: “Black Holes” for Gains?

Some argue the rapid growth of these conversions shows ETF tax advantages legal but expansive are being pushed beyond the spirit of taxing investments upon sale. Jeffrey Colon of Fordham Law contends that enabling investors to rotate from tech stocks to foreign stocks or bonds without immediate tax is problematic: “We shouldn’t have vehicles that become black holes for capital gains.”

To curb tax-free diversification, the code’s 25/50 diversification test requires that no single position exceed 25% of the contributed portfolio and that the top five positions remain under 50%. Because the rule looks through to underlying holdings, many conversions seed with other ETFs to satisfy diversification before rebalancing.

Practitioner Robert Elwood (Practus) cautions issuers to seed with securities aligned to the fund strategy and to wait a “reasonable period” before selling initial positions ideally with a documented investment thesis. “Tax ownership” requires bearing the economic benefits and burdens; flipping seed positions the next day can look like transitory exposure.

Steven Hodaszy (Robert Morris University) argues the 25/50 test is insufficient, because investors can still achieve substantial diversification without recognizing gains an outcome he views as policy-wise unjustifiable.

Momentum and the Macro Bill

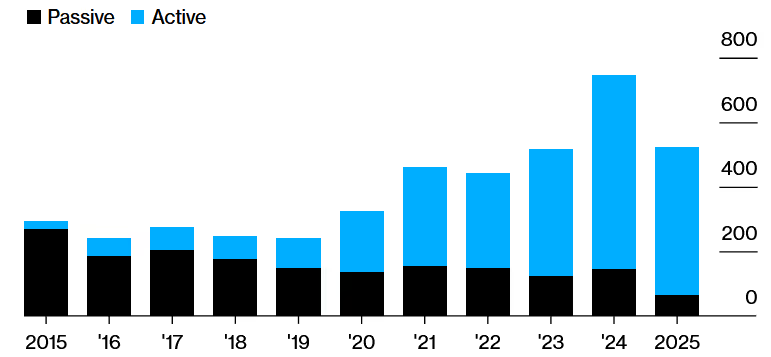

Tax minimization ties with wealth preservation as a top priority among advisors to high-net-worth clients. Conversions are just one strand of a wider tax-engineering toolkit including funds designed to avoid distributions, long-short loss harvesting, and income-tax-aware strategies. The ETF wrapper’s flexibility has fueled a record pace of launches, with active ETFs—the bucket where most conversions land making up an unprecedented share of new products.

Historically, ETFs realized annual capital gains around 4.1% of assets but distributed only 0.12% in taxes; passive and active mutual funds distributed 2.1% and 3.7%, respectively. Extrapolations suggest $1.4–$2.5 trillion of capital-gains tax could be deferred over the next decade on current U.S. equity ETF balances. As Rabih Moussawi (Villanova) asks: if more gains are deferred, who funds the shortfall in federal revenues?

Final Take: The Silent Revolution in ETF Tax Strategy

Section 351 conversions reveal how financial innovation always finds the cracks in the system. What began as a niche tax-deferral tactic for a handful of wealthy investors is now quietly reshaping how portfolios are rebalanced and wealth is preserved. Whether you view them as creative efficiency or regulatory loophole, these structures highlight a simple truth: the biggest alpha isn’t always in the market it’s often in the tax code.